The “real estate of the future” is riddled with faulty software, empty servers, and vast opportunities for abuse.

AFTER FACEBOOK’S REBRANDING to Meta, a series of stories about digital land rush began. Investors were buying up land in cyberspace, sometimes for millions of dollars, apparently convinced there must be gold in it in the hills of the metaverse. And if so many people with so much money rushed, it must be because a profit can be made. Right?

However, the language we have been using to discuss this new phase of technology, describing it in terms of a singular metaverse with a finite space to develop, has helped hide a reality that is more like early access video games and common bombs. and dump schematics.

The Narrative

It’s only been a couple of months since Facebook’s rebrand, but it’s hard to overstate how much it’s fueled the conversation about “the metaverse.” To begin with, almost everyone describes it as the metaverse, when the reality is that there is no singular metaverse in the sense in which we speak of “the Internet”. Services like Meta’s Horizon Worlds and Microsoft’s Mesh don’t interact with each other, they’re just separate VR apps.

The problem with this language quirk is that it can give the impression that, for example, if a company says that its virtual reality app, video game, or social platform is part of the “metaverse,” then that specific app must be where this future is. hazy will pass Which is a bit like saying that augmented reality is the future, and Google Glass is an AR product, therefore Google Glass is the future.

Under this implicit framework, stories published everywhere from cryptocurrency enthusiast sites to Business Insider to The New York Times have touted a “virtual land boom,” highlighting the $2.4 million sale of a 116-acre property. parcels in Decentraland, while investors invest millions of dollars. dollars in virtual locations. In these articles, executives at the Metaverse Group, a self-described “virtual real estate” company, described buying land in “the metaverse” as similar to buying property in Manhattan long before the city was developed.

More precisely, platforms like Decentraland or Sandbox sell NFT-based tokens that point to sections of a map in their specific virtual worlds, but those spaces don’t intersect. As Dan Olson, a video essayist who has extensively covered online social experiences and movements, from Fortnite digital concerts to Flat Earth to QAnon, and is currently researching the cryptosphere, explained to WIRED: “They are selling their tokens that give you permission. to build within your space. So you are effectively buying their service.”

In other words, buying “real estate” on these platforms is like buying a property in Manhattan, but in a world where anyone could create an infinite number of alternative Manhattans that are just as easy to get to. Which means that the only reason users buy this Manhattan is if it offers a better service than the others.

In most aspects, these platforms resemble your average video game. You control a customizable 3D avatar with your mouse and keyboard (no VR or AR here) and navigate a virtual environment. The debate over whether a virtual social world counts as a video game is as old as Second Life, but whatever you call them, the main new innovation in them is the use of NFTs and cryptocurrencies.

Decentraland’s argument is that using NFTs makes land in their game world scarce and therefore valuable. You can own some of the land, the value of which will increase as demand for the space increases, at which point you can sell it. Alternatively, you can rent space on your property to brands that want to advertise, host events and get a share of the sales, or open a store and sell digital items to users.

The language that investors, and even the media that covers them, use to describe this type of development echoes real-life real estate terminology. A press release from Tokens.com (which owns a 50 percent stake in the Metaverse Group) said the company opened “digital ground” in a tower in Decentraland, a phrase echoed by The New York Times in its report on the story, and that the tower is “under construction” on parcels of land owned by the Metaverse Group.

However, this is an unusual way of describing the process of designing 3D models or virtual environments. As software engineer and crypto skeptic Stephen Diehl explained to WIRED, this kind of language can be more about building a story than describing a technical process. “People need to have a narrative behind this. Because at the end of the day, you’re just buying numbers on a computer,” he said.

“The story that you are buying something in a new skyscraper or in a building is largely some kind of hogwash.

The Reality

Decentraland is a browser-based service, and while it’s been selling virtual land since 2017, the virtual world itself has only been open to the public since February 2020. Inside, it’s still reminiscent of an Early Access game. While the initial lobby where users first enter often has a dozen players wandering around, with many more completely immobile, the map shows only small groups of players gathered around a few key areas. The rest is largely empty.

I visited the “Fashion District” in Decentraland, which occupies a large chunk of land in the far west of the map, divided down the middle by a road. Most of this space is covered by the predetermined procedural terrain, with the main exception being a row of Graben-style buildings in Vienna. Digital ads for brands like Chanel, Dolce & Gabbana and Tommy Hilfiger adorn the sides of the buildings, but you can’t go inside. There are no stores here, nothing to click or buy, and it’s unclear if these brands approve. or even know that their logos and designs are in use.

The space feels less like a bustling up-and-coming mall and more like a movie set, a facade for what might happen to this place one day, but is gone now. The 116-parcel property that sold for nearly $2.5 million is just south of the empty storefronts and stands completely empty. For all intents and purposes, it is a ghost town.

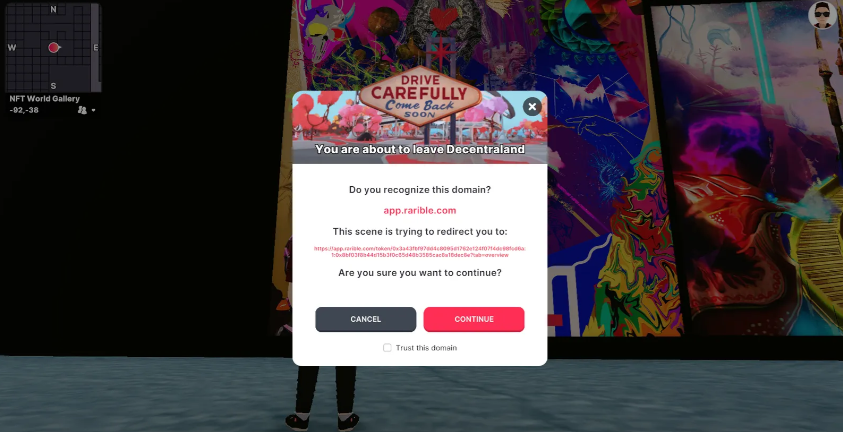

There are stores elsewhere in Decentraland, but only by a vague definition of the word. Several galleries display NFT artwork, including a Sotheby’s exhibit, where you can walk up to a piece and click on it. However, you cannot buy it within Decentraland. Instead, you will be redirected to an external website in another tab that can actually handle the transaction, usually a pre-existing store for NFTs like OpenSea or Rarible. At that point, it’s easy to get distracted by exploring the site itself.

“This is part of the old, old, old critique from the 90s of this concept of the 3D web,” Olson said. “There’s a part of our brain that says, man, it would be a lot more interesting if the experience of going to Dominos.com was more tangible. And that’s not bad. It would be more interesting. But you know what else it is? It’s also more inconvenient.”

Even if Decentraland could attract luxury fashion brands to build storefronts in its virtual world, those storefronts are only useful if there are users to sell to. But it’s hard to get a real idea of how many people are active in Decentraland. A tracker that shows how many people are online at any given time rarely showed a much higher concurrent population than around 1600 people over the several days I spent inside. However, the game fails to boot for players who sit idle for too long. I was logged in for an entire work day and overnight and never logged out. This makes it hard to say for sure how many “active” users are actually people who left with a tab open.

The game (for lack of a better word) itself is buggy and the moderation tools are broken or non-existent. In Decentraland, players can use voice chat to talk to anyone nearby, but the filter to restrict this to “friends only” has a beta tag and often didn’t work for me. Blocking a user will prevent their messages from appearing in the chat, but their 3D model is still physically present in the space and there is no way to prevent them from following you.

A basic profanity filter censors certain chat swear words and display names (and some obvious slurs will be censored even if a user turns the filter off), but users can also pay to mint NFTs to get a unique avatar name without needing to. of extra. Tags “#1234” at the end.

According to Decentraland’s Marketplace (which also lists user-owned NFTs that are not currently for sale), several players currently own NFTs that contain slander. Four contain the N-word and two contain the F-word, one of which has both. And since these are NFTs, they can be traded or sold just like any other. At the time of this writing, the name “Jewish” was for sale for the equivalent of $362,000.

In a normal game, one might expect developers to ban users or block offending usernames outright. However, Decentraland advertises itself as being run by a Decentralized Autonomous Organization (or DAO). This partially automated system uses “smart contracts” to automatically execute certain tasks based on votes from community members who have a financial stake in Decentraland. The more money members have invested in currency or land, the more voting power they get.

One of these smart contracts governs the list of banned names, which can only be changed by a community vote. In one case, the community voted to ban the name “Hitler” (51 votes to 15), but since the vote did not reach a high enough threshold of voting power, the vote failed and the suggestion was rejected.

A December 6 Decentraland blog post reported, among other things, that a survey to add the N-word to the list of denied names had passed successfully. Since the word can still be found in the Decentraland Market, it is unclear if this was implemented or if it applies to already minted NFTs.

In the future, luxury brands may have storefronts in virtual worlds where users can browse their stores as if they were walking through a real store. But between buggy software, a minimal user base, and a system that allows users to buy and sell slander with only a convoluted governance system to potentially stop them, the odds seem stacked against this platform being the one to build them. .

And yet investors seem to believe there is money to be made here.

The Money

Decentraland’s big point is that users can “buy land” in-game, but the process for doing so is complicated. Users cannot purchase land tokens directly with regular dollars. Most can’t even be bought with ether, the popular bitcoin alternative. Instead, like many crypto projects, Decentraland has its own cryptocurrency called mana, technically an ERC-20 token, a type of digital asset, which means that while Decentraland is built using the Ethereum blockchain, the price of mana it can be much more volatile than ether.

Currently, the cheapest plots of land in Decentraland typically sell for around 4,000 mana, which at the time of writing would cost almost $15,000. However, once a user buys a piece of land, they own that asset until someone wants to buy that specific piece of land; after all, tokens are not fungible. On the other hand, mana is fungible, which means that if a user has large amounts of mana, they can sell those tokens to anyone who needs to buy mana, including any new users who may have shown up to buy land.

Since land is so expensive and the mana market so small, it doesn’t take a lot of activity to move the needle on the price of either. “If you issue a press release, will that change the price of ether? Yes, it could alter the price of ether,” Olson explains. “But you know what will definitely alter the price, it’s the price of mana and the price of land.”

This has already happened with mana a couple of times. In the two days after Facebook’s rebranding to Meta, the price of manna, which had, at the time, rarely exceeded $1, skyrocketed to $3.71. At the time, the media, starting with niche crypto enthusiast sites like CoinDesk, then CNBC, reported on the rising price of manna and interpreted it as positive interest in “the metaverse.”

A few weeks later, on November 22, the aforementioned 116-parcel “estate” in the Decentraland fashion district was sold for 618,000 mana. The following day, Tokens.com issued a press release announcing “the largest metaverse land acquisition in history,” which was picked up by several crypto sites as well as Reuters and the National Post. When the press release was issued, the price of manna was around $4.10.

Two days later, the price of manna had risen just over 41 percent to an all-time high of $5.79.

Whether the space in Decentraland was ever valuable as virtual shops or event venues, the currency used to purchase that land more than quintupled in value in about a month.

While rising numbers are not inherently evidence of a nefarious scheme, the rise in crypto-pump-and-dump schemes should at least be a call for skepticism. On the day mana hit its all-time high, transaction volume in the token exceeded $11.4 billion, completely eclipsing the $2.4 million spent on a land sale.

It may be the case that Decentraland, or other similar virtual worlds, are the future of the internet. But if they aren’t, then huge amounts of money have already been invested in their systems, and someone is going to get the bag. And because of the narrative around many of these “metaverse” projects, that the future of the internet is in this specific space, and if you buy now, you can own the next digital Manhattan, those who argue that bag could end up being average people who were just fooled by a good story.

Those narratives are typically told through press releases, company announcements, or news coverage where the only voices present are the ones that stand to gain the most. But, as Olson explained, the audience for those stories are people who have a lot more to lose.

“Their target is the tenuous middle class. People who feel that the system is squeezing them and feel that their solvency control is slipping away. Who feel like the gig economy is strangling them. And they’re pitching them with, ‘Here’s your chance,’” Olson said. “‘You just need to bet in the right currency. You just need to bet on the right meme at the right time. You just need to bet on the right ape and you can cash out. You can escape.’”