The metaverse is coming. It was once a science fiction fantasy, most notably in Neal Stephenson’s novel “Snow Crash,” of an all-encompassing virtual universe that would exist alongside the physical one. But technological advances have brought this transformation of human society close enough to reality to demand that we consider its consequences.

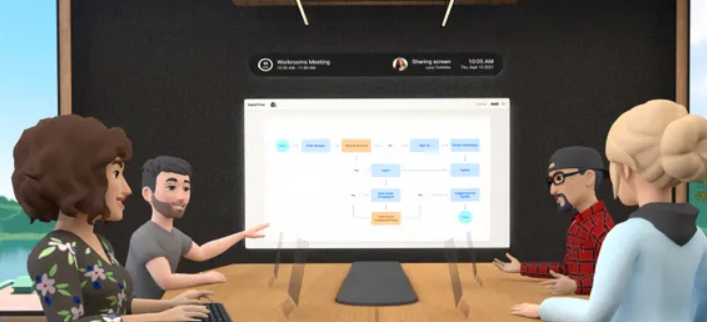

In the metaverse, a user can select a digital avatar, like a character in a video game. Through the eyes of their avatar, they would experience a digital reality as active and engaging as the physical one. Some futurists believe that we could soon attend medical appointments or classes there.

But while the metaverse could revolutionize work and play, it’s essential to remain alert to the dangers that will arise if it subsumes daily life.

Virtual environments will enhance disinformation, espionage and surveillance campaigns. Fights for control of the physical infrastructure of the metaverse could very well exacerbate global conflicts. And the supranational nature of the metaverse, where real-world borders become much less relevant, could revolutionize the way individuals perceive and interact with nation-states.

Failing to anticipate these possibilities may put the global world order at risk of being replaced by a virtual, and perhaps less virtuous one.

Today, glimpses of the metaverse are everywhere. Virtual concerts draw record audiences; high-end designers sell virtual fashion; and games have become a livelihood for people all over the world. Many of the closest corollaries to a full metaverse are immersive games like Fortnite, Minecraft, and Roblox, where players can socialize, shop, and attend events in a virtual world.

There is already evidence that online multiplayer gaming can enable the spread of misinformation and conspiracy theories. Players can use in-game communication tools to spread rumors or “fake news”, targeting others in hard-to-trace ways.

The metaverse could allow motivated regimes or extremist groups to go a step further. Immersive layers of text, voice, and images in virtual environments would provide compelling new ways to deliver misleading or extremist content.

In environments where people can be represented by pseudonymous avatars, knowing who to trust with sensitive information will be even more difficult. This could pave the way for a new era of espionage.

Dozens of countries have already used digital espionage to gain access to commercial intellectual property, proprietary military technology, and personal and financial information. A metaverse containing nearly every aspect of life—work, relationships, assets, identity—could be susceptible to breaches or manipulation around the world.

It is likely that countries and corporations could also use the metaverse to engage in surveillance with greater sophistication.

States have already used facial recognition technology to monitor people’s behavior. Companies have used it to unlock devices or animations in real time. Integration with the metaverse could make it, and the privacy concerns it presents, even more ubiquitous. If exploited, that technology could easily be used to monitor any participant around the world.

Even the physical infrastructure of the metaverse will likely present new vulnerabilities.

A constellation of technologies, including hardware, computer networks, and payment tools, will support the functionality of the metaverse. The countries that maintain control over those technologies will have significant international influence, just like the countries that dominate things like transportation routes or oil supplies today.

China could effectively control the backbone of the metaverse in many corners of the world, thanks to its Digital Silk Road initiative, which finances the telecommunications systems of some countries. Taiwan, which dominates the semiconductor industry that supports computing needs, is likely to become even more of a lynchpin on the global stage.

This type of physical infrastructure, in turn, will be vulnerable to hacking and supply chain disruptions. If people own, earn a living, and maintain communities in the metaverse, hardware shortages or service outages could jeopardize livelihoods or undermine social stability.

Despite these threats, the metaverse also has the potential to improve global affairs. International diplomacy can easily be carried out in virtual embassies. Smaller, less powerful nations may find themselves on a more level playing field, better able to stay in the mix on global affairs or perhaps forge unlikely alliances.

Virtual environments have also shown promise for activists resisting digital authoritarianism. In Minecraft, Reporters Without Borders has sponsored an Uncensored Library where users can view content from dissident writers that has been censored in countries like Saudi Arabia, Russia and Vietnam. The metaverse may bring a new promise of freedom and transparency across borders.

But the consequences of the metaverse may be even more radical.

If it becomes as comprehensive as some predict, the metaverse may foster virtual communities, networks, and economies that transcend borders and national identities. People may one day identify primarily with metaverse-based decentralized autonomous organizations with their own quasi-alien politics. Such a transition could require reconceptualizing geopolitical issues from the ground up.

The metaverse may have been born in science fiction, but it’s up to us to write a future based on clear reality.