Mark Zuckerberg wants us to think of visual art when we contemplate his company’s new venture. Artists should take the suggestion seriously.

In the first pages of Ben Lerner’s debut novel, “Leaving Atocha Station”, his narrator goes to the Prado museum in Madrid and observes a stranger breaking down in sobs in front of Rogier van der’s “Descent from the Cross”. Weyden, a votive portrait attributed to Paolo da San Leocadio and the “Garden of Earthly Delights” by Hieronymus Bosch. He watches the man until he leaves and follows him into the sunlight. The narrator has long worried that he is incapable of having such a profound experience of art. Many of us, I imagine, have experienced the failure of being moved by a painting as we had hoped. I thought of this passage while watching Meta’s first major announcement, Facebook’s rebranding as a metaverse company, also taking place in a museum. But here the art is moving, literally.

The video opens with four young men watching Henri Rousseau’s “The Fight Between a Tiger and a Buffalo,” which is on display at the Cleveland Museum of Art. As they look into the frame, the tiger’s eyes blink and the entire painting comes to life, opening up into a three-dimensional animated jungle. The tiger and the buffalo, the toucans and the monkeys and the baboons in the trees all begin to dance to an old rave tune; children also dance. Fruit trees grow around you on the gallery. Above the rainforest canopy, in the distance, is a mysterious hexagonal portal, and beyond, in the misty red hills, the imposing skyline of a large tropical city. It’s a scene that suggests Facebook may be returning to Silicon Valley’s counterculture origins: a psychedelic dream of a global community sharing collective hallucinations.

The video keynote Meta released to explain itself to investors also highlights the art, starting with a demo in which a couple of Mark Zuckerberg’s coworkers find a piece of augmented reality street art hidden on a wall in SoHo. . Brought to life by 3D animation, he transferred from Lower Manhattan into virtual reality, becoming a kind of nightmarish Cthulhu surrounding his avatars. (Zuckerberg: “That’s awesome!”) For some reason, the company wants us to think of art when we think of its new product. Maybe it’s because they want us to see it as a platform for creative self-expression, or maybe just because fine art provides a more uplifting context than gaming or working from home.

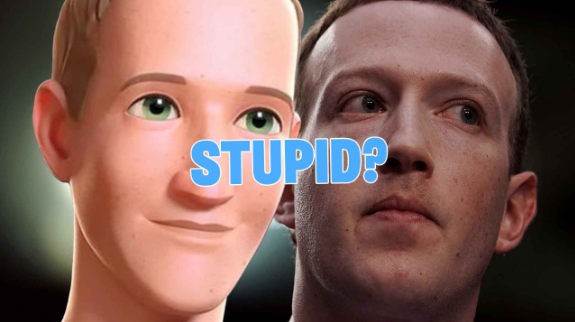

This apparent stance toward art is both stupid and on point; silly because it reduces art to a mere trinket, apt because other entrepreneurs have already embraced this view. The animated Rousseau assumes the popular logic of the “Van Gogh immersive experience,” in which the dour old Dutchman’s paintings of starry nights and ominous wheat fields are projected onto walls and floors to create an immersive spectacle, an attraction and a backdrop for selfies. Both assume that works of art can be enjoyed by the public only when they are in the process of going bankrupt. And in the case of the Van Gogh experience, the market has proven them right: there are currently at least five different competing Van Gogh experiences touring the country. The copy has surpassed the original. This has been a consistent theme throughout Facebook’s history, offering a pale simulation of friendship and community rather than the real thing. Meta promises to take us further into the forest of illusions.

And yet, a return to an art of dreaming and escapism is a tempting proposition. Rousseau, painting jungles in his Paris studio beginning in his middle age, was escaping his own monotonous life as a retired municipal employee of the toll service. It is said that he often told stories of his youthful adventures and how his tour of duty in Napoleon III’s intervention in Mexico had inspired his jungle pictures; but all these were lies. Actually, he played in an infantry band and never left France.

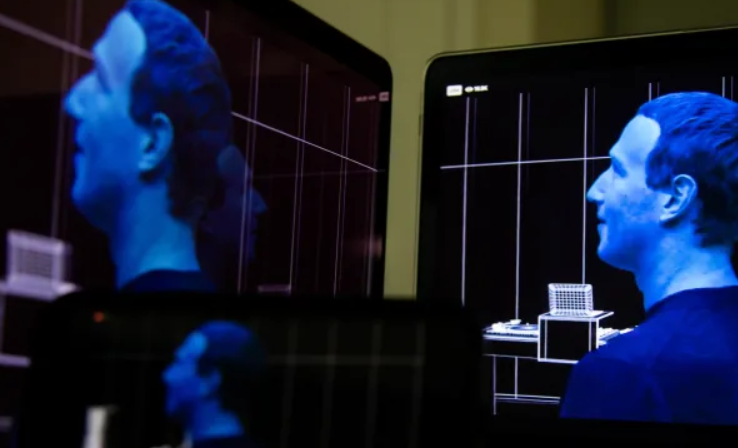

An important thing to remember about the metaverse is that none of this has been made, neither the jungle nor the technology to display it.

Rousseau found his real inspiration in travel books and regular visits to the Jardin des Plantes, of which he once told an art critic: “When I go into the greenhouses and see the strange plants from exotic lands, it seems to me that enter a dream.” It was this strange dreamlike space, where ferocious animals have the quality of children’s book illustrations and bananas grow upside down on the trees, that he conjured up in his paintings; and it was the childlike originality and naive purity of these depictions that his fellow artists would come to admire.

In the Paris of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Rousseau and his contemporaries (Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat, Pablo Picasso, etc.) dedicated themselves to inventing bohemian modernity, creating new ways of living and seeing the world. In our century, that visionary role seems to have passed from artists to engineers, to Zuckerberg and his ilk. Who else tries to invent new universes? Who dares to weave great utopian fantasies? The artists no longer. It’s the Silicon Valley founders of Promethean who try and often come up short.

Meta’s offer is not attractive: it is somehow both childish and cynical. But a vision of the future dreamed up by a creative agency for a megacorporation was always going to be terrible. The problem is not that today’s children cannot appreciate a Rousseau masterpiece, but that their elders, my generation, are not sure how to find anything that can compare with it: we have forgotten how to imagine a completely different world.

One important thing to remember about the metaverse is that none of this has been done, neither the jungle nor the technology to display it. You can’t really go to a museum and do this. It’s just an idea, a whisper in the wind. An ad about nothing. is goal. The more times I see the ad and keynote where Zuckerberg explains his vision in detail, the more it seems like he has no idea what he’s doing or selling. That’s bad for a company, but not for artists, who thrive on an open mandate. In fact, much of the keynote is a call for thousands of “creators” to help build a working metaverse, and a promise that they’ll get paid to do so.

Contemporary art is currently dominated by painting and sculpture, by traditional materials and ancient ways of doing things. Meanwhile, companies outside of the art world are using digital technology to remake timeless masterpieces as vanishing tricks, projected tourist attractions, and animations. But few artists are doing what Rousseau and his peers did: accepting the realities imposed by new technologies, in his case photography, and breaking old habits to create something new. An artist in the spirit of Rousseau might appreciate the potential of this new medium and want to make art for the metaverse and the general public. Now, as in his day, he would not be redoing old works from the past, but creating fantastic scenes from his dreams: sights he had never witnessed in his own life, rendered in a style no one had ever seen. Today it feels possible, perhaps for the first time this century, to invent a whole new aesthetic, provided someone takes the reins from the technologists.