On the eve of the new year, a tragedy occurred in Manhattan: Chelsea art gallery owner Todd Kramer had 615 ETH (about $2.3 million) worth of NFTs, mainly Bored Apes, and Mutant Apes, stolen by scammers and peer-to-peer listings. OpenSea NFT Marketplace.

Kramer quickly took to Twitter and asked OpenSea and the NFT community for help in getting his NFTs back. Unsurprisingly, he was trashed by other members of the community for not storing his valuable JPEGs in an offline wallet; however, OpenSea froze trading of the stolen NFTs on its platform.

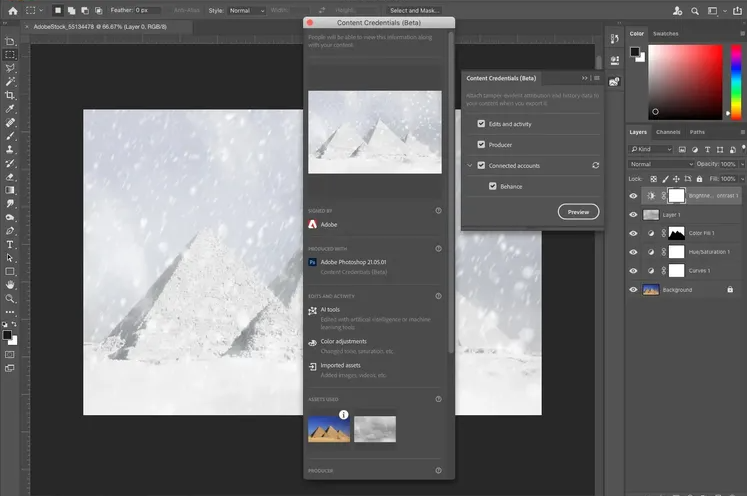

Quite a few commenters pointed out that OpenSea’s intervention here, and especially Kramer’s pleas for a centralized response, seemed to run counter to a key industry principle that often clashes with usability: the idea that “code is law”. “, and once your tokens are in someone else’s digital wallet, that’s game over. While OpenSea did not actually reverse the transaction on the blockchain, it did block the sale of stolen NFTs on its own platform, which is the most popular marketplace for NFTs.

“We take theft seriously and have policies in place to meet our obligations to the community and deter theft on our platform. We do not have the power to freeze or remove NFTs that exist on these blockchains, however, we disable the ability to use OpenSea to buy or sell stolen items We have prioritized building security tools and processes to combat theft at OpenSea, and are actively expanding our efforts in customer service, trust and safety, and site integrity so that we can move faster to protect and empower our users.”

He did not answer, however, why he had frozen the marketing of these NFTs and not others stole just a few weeks ago that were announced on Twitter by the NFT owners of Bored Ape Yacht Club and Jungle Freak

OpenSea in the lurch. For example, another Twitter user recounted in a viral post how they unknowingly bought a stolen NFT on OpenSea for 1.5 ETH (around $5000) only to freeze it. OpenSea was not quick to help them, they said: though it’s not clear what they could actually do for the company at the time, and the Alien Frens NFT project reimbursed them 1 ETH.

In these and other cases, “self-sovereignty” is offered as an attempt to reframe what really happened. Yes, victims are ridiculed for being Victims of a hack or scam, but they are expected to learn from their mistake by using cold storage and, in the best case, can buy back the NFTs at a discount because they are not sold in major markets. had a centralized intervention. Kramer himself was able to buy back at least two of his NFTs with the help of users who had unknowingly bought them from the scammer.

OpenSea’s interventions in stolen NFT cases show how centralized intermediaries often play an important role where the decentralized world of the blockchain meets the real world. It’s also not the first time similar moves have taken place elsewhere in crypto, even though they break with the core dogma of immutability and self-sovereignty.

In 2016, a hacker stole nearly $60 million worth of ETH, the equivalent of 5 percent of all ETH in circulation at the time, from an early DAO on Ethereum, simply called The DAO. To return the ETH, the developers reversed the transaction and deleted it from the blockchain ledger with a hard fork, creating a new version of the blockchain. Users started using the new ledger that returned their ETH, while the original was dubbed Ethereum Classic (ETC) by people who bristled at the idea of forking to save hacked funds. In 2019, when hackers stole 7,000 bitcoins from cryptocurrency exchange Binance, the founder, Changpeng Zhao, suggested something similar happen and enact a hard fork to reverse the cyberattack.

Tether (USDT), a stablecoin that claims its currency is pegged 1:1 to the US dollar, routinely “freezes” tokens at the behest of regulators or law enforcement. It recently froze $1 million by blacklisting an Ethereum address, but it also has a “take back” mechanism that allows you to freeze an address where funds were sent in error and issue a new USDT.

Scams have always been a part of the cryptocurrency industry, as has the uncomfortable issue of centralized interventions. A recent study found that 50 percent of all tokens listed on the popular decentralized exchange Uniswap are outright scams. Last month, CoinDesk proudly defended OlympusDAO as the “future of money,” admitting in the first sentence of its defense that “Yes, it’s a Ponzi scheme.” Scams and thefts in the decentralized finance space have continued to worsen, reaching $14 billion in 2021.

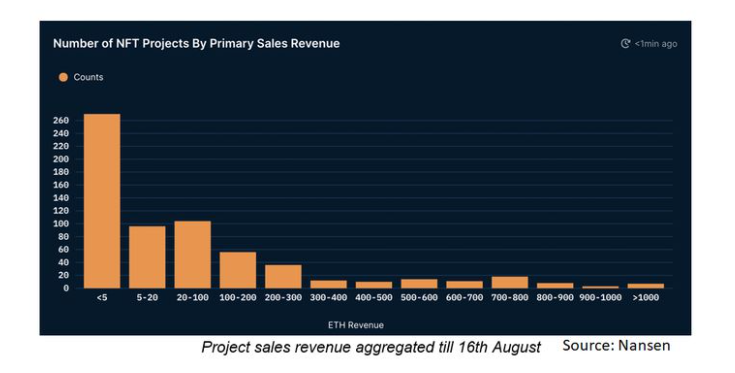

Increasingly, it appears that inconsistent application of rules in this space often results in protection schemes. wealth transfer instead of protecting all users equally and obscuring the deep centralization already present: Less than one percent of users (institutional investors) account for 64 percent of Coinbase’s trading volume, and 10 percent of merchants account for 85 percent of NFT transactions and trade 97 percent of all NFTs at least once.

It is not clear how this contradiction will be resolved. Uncritically believing that decentralization is a balm that immediately transforms the politics of something and endangers not only users but also the fever dream of cryptocurrency disruption. Take the adoption of blockchain-based technology by central and investment banks as an example. One way to see this is as a sign of the inevitability of cryptocurrencies. However, if you look under the hood, it is more clearly a move by financial institutions to bolster fiat and further centralize the global financial system.

As long as the contradiction persists and the uncritical belief holds, crypto will find itself in an increasingly weak position to do anything about any of these concerns.