If you have an Internet connection, you’re probably familiar with the feeling. Something new starts to happen online. People seem really excited about it. You suddenly feel curious. (Sure, I’ll join TikTok.) Or maybe you are terrified. (Is it too late to buy crypto?) Everyone at some point fears missing out on something.

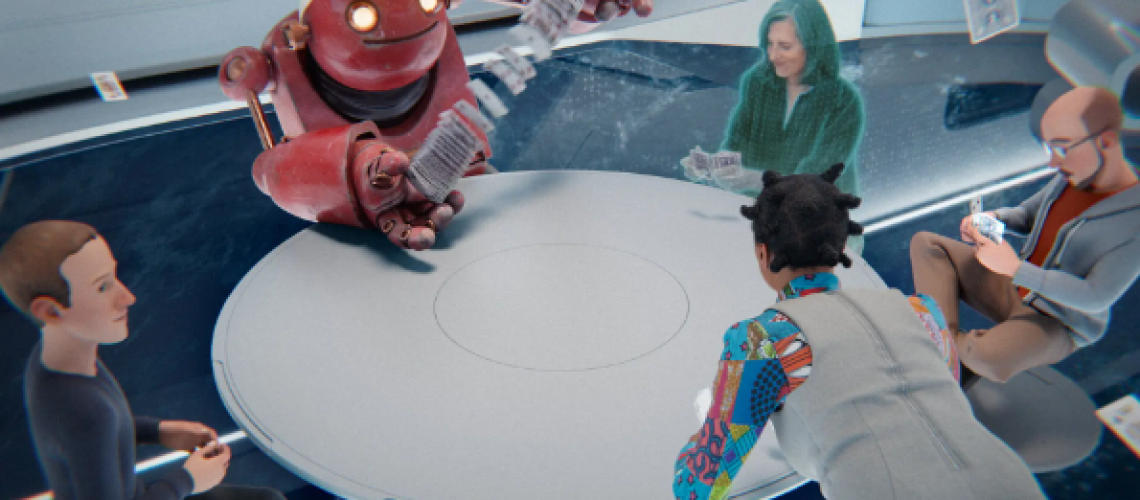

Speaking of which, have you heard of the metaverse? Even if you didn’t tune in to Mark Zuckerberg’s 81-minute video disquisition last week on the future of human interaction, culminating in Facebook being rebranded as Meta, the term has been bubbling up this year. Leaders in technology, entertainment and fashion have been quick to claim it, though few seem to agree on what exactly it is. The important thing is that it arrives.

Conversations about the metaverse reduce the feeling of FOMO to its most basic and pervasive form. “Metaverse,” the term, was coined by Neal Stephenson in his 1992 novel “Snow Crash,” and has recently been put into such wide and varied use that it has come to mean something no more specific than the future. Who wants to miss that?

Well, to be fair, a lot of people. And they have their reasons. For now, talking about the metaverse is mostly a branding exercise: an attempt to unify, under one conceptual banner, a lot of things that are already taking shape online.

Matthew Ball, a venture capitalist writing about the metaverse, described it as “sort of a successor state to the mobile internet,” which is helpful in demystifying: the metaverse describes the way various emerging technologies (cryptocurrencies, NFTs, gaming online) platforms like Roblox and virtual and mixed reality hardware, including Facebook’s Oculus, for example, can grow and overlap. In the words of Mr. Zuckerberg: “I think the metaverse is the next chapter of the Internet, and it’s also the next chapter of our company.”

As a point of comparison, Mr. Ball often looks to the era of smartphones, which changed our relationship with technology in ways as profound and impactful as they now seem banal.

Think back to 10 years ago, when smartphones and apps were new and social media was booming. Many people believed that the era of the pocket supercomputer would change, well, many things, even if they didn’t quite know how. The boosters of the metaverse, who may seem eager to shed the baggage of the last age, believe that we are on the cusp of even greater change.

If this sounds more linear than visionary, despite the brand of sci-fi and “decades from now” talk, that’s because it is. Fortnite has over 300 million players around the world, many of whom view it as a way to hang out with friends and engage with the culture at large. Cryptocurrencies and NFTs are only speculative in the financial sense: they exist and you probably know someone who owns them. There are tens of millions of VR headsets in circulation now, mostly for gaming. Give him an oportunity. They are interesting!

You might even consider the absolutely obvious ways the internet has become more present in your life, pointing in the overall metaversal direction. The way you’ve cultivated people online in different contexts, on Instagram, LinkedIn or Slack. The way you play Scrabble on your phone all day, wherever you are. The sad virtual office of the Covid Zoom routine. The group talk!

Using a label like “the metaverse” has the strange effect of making things that are already happening sound far off and impossible. People are actually spending enormous amounts of time and money in rich, game-like interactive spaces with their own cultures and economies. Entrepreneurs are really building an alternative financial system using blockchain technology, buying and selling virtual real estate, and trying to figure out how a placeless, stateless system could govern itself.

As several technology writers have pointed out, Zuckerberg’s argument is not particularly novel. (Any Roblox fan in your life could have told you that.) The label also provides a slippery subject for criticism. If any of these trends worry you, don’t worry! Everything will be better when we are really in the metaverse.

For all his gestures about a vague future yet to be built, Zuckerberg’s attempt to explain and reclaim the metaverse made one thing clear: the strongest FOMO could be his. For someone whose company can genuinely be said to have changed the course of history, becoming central to the lives of billions of people, the prospect of another new Internet age could be downright terrifying.

It’s not lost on the early winners of the social media age that a lot of what people are excited about online right now, pretty much anything that promises a “decentralized” experience, is, by definition, positioned against big companies like Facebook. (This would also explain why Zuckerberg spent so much time talking about virtual reality, where Facebook has a real foothold.)

Not missing out on the latest breakthrough is what made technology leaders and their companies what they are. Missing out on the next big thing, whatever it is, is not an option. Giving various promising and threatening trends a unifying name is more comforting, from this point of view, than watching the chaos of dozens of competing technologies adopted by billions of people hurtling in directions that even the most prescient visionaries will get a little bit right. .

As Benedict Evans, another venture capitalist, wrote in October, the current metaverse discourse is “rather like standing at a blackboard in the early 1990s and writing words like interactive television, hypertext, broadband, AOL, multimedia.” and maybe video and games. , and then drawing a box around all of them and labeling the box ‘information superhighway’”. (Her former employer, crypto-forwarding firm Andreessen Horowitz, where a designated partner sits on Facebook’s board, has leaned more towards the term “Web3.”)

Today’s tech giants have industry-grade resources, talent, and FOMO on their side, so it would be a mistake to underestimate their influence on this supposed successor state of the internet.

However, there are two predictions I feel comfortable making about the metaverse.

One: it won’t be known to the people who inhabit its vast, distinct, as-yet-to-be-determined environments as “the metaverse.” If we’re actually doing our work in virtual offices, we’ll just call it work.

Two: For most of us, missing out on a more fully connected lifestyle, where identities, work and sociability are further blended in physical and virtual spaces, many designed with profit in mind, won’t be the problem. It will be to find out if we can leave.